Review (Published in Drain: A Journal of Contemporary Art and Culture, Issue: Athleticism, July 2015)

Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try Again. Fail again. Fail better. —Samuel Beckett

Out of Tune

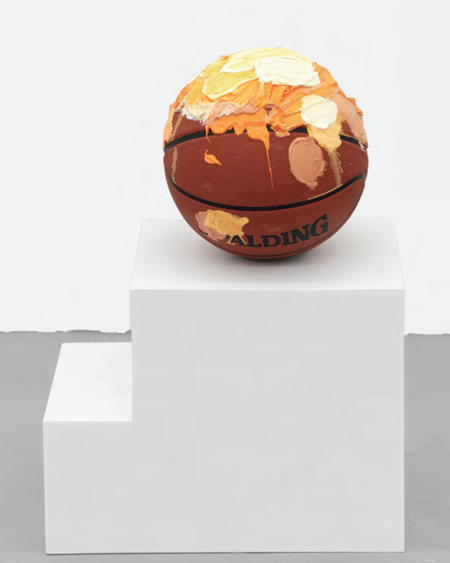

Beckett’s quote on failure, professional basketball and The Bard of Avon all mingle together inside the studio of visual artist Craig Drennen. This unusual framework and language shaped his recent exhibition ‘Poet and Awful’ at Samsøn gallery in Boston, Massachusetts (October 31st–December 24th, 2014). The work consists of paintings, sculptures and performances and is based on the list of characters in the Shakespearean play Timon of Athens. The exhibition combined the characters in the play with the vernacular language and value system of basketball.

The play Timon of Athens is centered around the character Timon, a wealthy man in a thriving affluent city who spends his entire fortune frivolously on friends who later turn against him until he becomes a misanthrope. If you have not heard of Timon of Athens, despite what you may have considered a good working knowledge of Shakespeare, you are not alone. Some consider the play his weakest moment while others consider it his most difficult play. It was never produced during his lifetime and many scholars find aspects of the play unfinished and the many adaptations that have been performed have not proven to be among his popular works. The first character in the play is Poet. Poet says hello to everybody he meets and is embodied in Drennen’s paintings and sculptures. The second character in the exhibition is a mean-spirited philosopher who humiliates people in public with his superior wit. This character is embodied in a performance where Drennen (or a stand in performer) plays a Courtney Love song called ‘Awful’ over and over again using different instruments while wearing a large paper mache mask sculpture of a likeness of Drennen’s own head blown up to four times its size.

Drennen first came across the play after he read a passing reference to it in 2003 and then began to notice it in unexpected places. For instance, in Nabokov’s Pale Fire, titled after a term lifted from a speech in Timon of Athens. Drennen currently resides in Atlanta, Georgia in close vicinity to the Philips Arena where daily he sees the ‘Hello, welcome to Atlanta, home of the Atlanta Hawks’, sign. He made this literary structure a decided springboard for the characters in this series of works and influenced by this daily encounter with the arena, he made all of the Poet pieces say ‘hello’ in various degrees of loudness or friendliness or colorfulness of a sporting event. This is how these two languages were married to birth this character within the exhibition.

When we are young, we are often introduced to sports and told it is our participation rather than our performance that is the most important thing. But, we get older and those who excel and continue with it learn that practice, skill and performance are absolutely necessary. Drennen brings up that in both sports and art, there’s repetition, ‘And usually that repetition happens in isolation before you’re ready to go public with whatever you’re doing’.[1] He explained a big influence on his work method was the great humanist thinker-philosopher Erasmus of Rotterdam who believed that the true sign of intelligence wasn’t necessarily logic or memorizing data; it was being able to say something as many different ways as possible and in doing so to have the mental agility to intuitively have empathy for the situation and who your recipient is. This is sort of the opposite of the famous phrase that insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. It is stating that intelligence is doing the same thing over and over again and inventing different results working within context and timing. And it is not dissimilar to what actors do when, for example, performing the same play night after night for new audiences.

Drennen has stated he takes great solace in absurd things and this is quite clear. Viewing his work invoked a memory in me of when I first read Franz Kafka’s The Trial; Kafka’s novel that was published posthumously. In the story the character K. is arrested but not detained. He is told, ‘You are under arrest, certainly, but that need not hinder you from going about your business. Nor will you be prevented from leading your ordinary life.’ The sentence made me laugh out loud and I remember thinking, I am going to like this book. I also have vivid memories of my introduction to Shakespeare. I was in a drab unromantic back room of a library in my high school. Each play we read aloud as a group and a different student was assigned each role. There were daily occurrences of long pauses that ended with my teacher letting out loud exasperated sighs and calling out character names—’Mercutio? Mercutio? Who is Mercutio????’—because the student playing that particular role had fallen sound asleep on an open book. And we were in the good mainstream Shakespearian stuff, nowhere near Timon of Athens. Work that plays with varying levels of absurdity or plays on the parody of logic to enter into more serious discussion is work that I’m naturally drawn to. The word itself derives from the Latin absurdum that means ‘out of tune’, which seems fitting for Drennen’s ‘awful’ performances. But the genuine similarities between sports and Shakespeare outweigh the differences and the absurdity: the ‘prize’ competed for, planning and chance, desire, fear, social structure and limitation, recognition, mastery, confronting death, wanting a place in history, and of course love in all of its comic and tragic forms. These more serious topics rise in the Poet and Awful exhibition, once you get past Poet’s ‘hello!’

The Canon

A canon of works is often thought of as the most relevant, work that has official status. To enter the canon (or more properly, to be ‘let into’ the canon) is to gain this privilege. Works enter through institutions, influential people, scholars, and professors. Belonging brings status, an inferred guarantee of quality. For this exhibition, Drennen chose this obscure play as a structural framework—a specific choice within the repertoire of one who is considered by many as the greatest writer in history—which does not set the stage neutrally for the viewer from the beginning. It begins immediately to ask a question about our relationships with success, failure, performance, value, gift, worth and the canon. Drennen states ‘I choose “failed”‘ works, not because I’m interested in abject themes, but because their obscurity creates uninhabited cultural bandwidth that I can openly occupy. Timon of Athens is a corrupted text, of indeterminate history, questionable sources, and a dubious relationship to the respected canon. That is to say, it mirrors my own position within the art world perfectly.” When I asked Drennen about his relationship with failure he told me, ‘If a kite is well built but never receives any good wind and so never flies, I can’t say that the kite has “failed.” If a radio is fully functioning but is never put in proximity to a radio station, it seems like a failure but it hasn’t really failed. Failure, to me at least, just means that one condition wasn’t met’. So there is the work, the author, and the list of conditions, such as timing and audience. Drennen also states, ‘Anyone who says that they know who their audience is is either lying or delusional… There is no way to know. And it just seems terribly limiting to me’.

In these pieces Drennen creates a carefully crafted code, multilayered and cryptic. For example, the twenty-four that appears in all of the paintings immediately made me think of 24 hours in a day. But Drennen was thinking of when the clocks changed to 24 seconds in professional basketball in 1953. He uses the characters and some very specific things about the characters, but not the plot or story; he brings us into this work under the guise of a narrative but then breaks it apart. He uses a story but does not keep any story structure there for us. Every good storyteller creates a believable universe that the viewer can stand in and this is often done so by carefully crafting details, systems, and rules of that universe that we remain within. This invisible encasing is there and the invention happens within that encasing, suspending our disbelief. The works in this series use this method of creating a believable world while simultaneously inverting it. This is a carefully crafted believable world without a story. And for me, when I enter it, a flood of my own and many other stories come to mind.

Drennen explained that the method an actor uses is very important and influential to him. ‘When I listen to actors or acting coaches, the idea of going on stage and doing three or four different characters, like in a one-person show, with different accents, different backstory, different everything, and having them all be believable—I think that’s extraordinary. That’s what I try to get paint to do. For me, to get the gestural part to be believable is a challenge. To get the representational part to be believable, that’s a challenge; to get the decorative part to feel natural … all these things are challenges that are more acting than painting. So it’s not really about any sort of binary of, like, abstraction and representation; it’s about acting’. Drennen’s paintings certainly enter into a conversation on levels of appropriation and he creates technical illusions using trompe l’oeil with his fluent command of paint. He has stated that he foresees this body of work to be a fifteen-year-long monologue. About Shakespeare, he says, ‘I will still attempt a gradual intervention into Timon of Athens until such time as it becomes mine instead of his’.

Trials

In all of these forms of work and stories, one of the big themes that arises is our struggle and search for meaning in life. Many believe that the search for meaning in life matters. And yet works, such as Kafka’s The Trial, address the question of whether the search for meaning in life matters. Drennen’s work holds this tone for me—but only for a moment—and then steps past it. Beyond that question, the work inventively and playfully presents other aspects and themes that arise within all of us in our games, our methods, and plays we perform that make us absolutely and unfailingly human. These areas are belonging, trying to understand ourselves and the people around us, trying to understand our choices and way of existing and how they range from poetic to awful and everything in between. This is what keeps me coming back to the work much more so than just to see who wins or how the play ends.