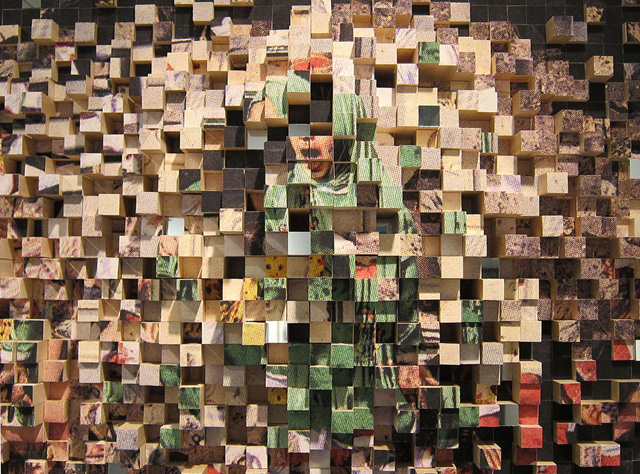

Shanti Grumbine, “The Gaze of Orpheus, December 7, 2012, A1” (detail) (2013), archival inkjet print, cut poplar dowels, mirrors, 44 x 58″ (all images courtesy the artist)

(Published July 17th, 2013 in Hyperallergic)

The title of Shanti Grumbine’s current exhibition at A.I.R. Gallery, The Glittering Point, comes from the phrase “glittering generalities,” which, according to the artist, became popular in the mid-nineteenth century. The term describes propaganda that champions vagueness to evoke positive feelings rather than actually communicating information. Grumbine begins her process with this phrase in mind, as she collects startling imagery of war, scintillating images of luxury items, and both iconic and candid political campaign photos from the New York Times. Once she has sourced the images, she removes, remakes, distorts, and even bedazzles them through drawing, printing, paper cutting, metallic painting, and the use of mirrors and glitter. The work denotes a point of communication breakdown in the media and holds us there while she transforms it. Grumbine alchemically shifts everyday media into an ethereal realm of mind and soul, taking something manipulative or horrific and raising it to the sublime.

The works in the exhibition — which come from three different projects: Kenosis (the ancient Greek word for emptiness or emptying), Admissions, and In Formation — explore the roles of text and image in the media by removing, erasing, and concealing. Grumbine makes her point with a voice that’s both poetic and primordial, employing the power of absence. It reminds me of the line of people who came to solemnly stare at the empty space on the wall where the Mona Lisa had once hung when it was stolen in 1911 (one visitor dropped a bouquet of flowers).

Many artists work with the symbols and imagery of the media in an attempt to demonstrate the profound effect they have on our minds and the use of subliminal persuasion and desensitization. Grumbine takes a more subtle approach, quietly walking past critique to remind us of the power of symbols as transcendental portals.

The largest piece in the exhibition is also the newest one, which Grumbine created for the show. She explained to Hyperallergic:

This new way of working grew out of the pixelated cut newspaper pieces, where I cut away at the images in a gridded pattern to combine printed media with a handmade digital pixel. The new piece, entitled “The Gaze of Orpheus, December 7, 2012, A1” is made up of 2,555 rearranged square pixels cut from a 44-by-58-inch blown-up digital print of the cover of the New York Times. It was a horrific photo of Shiite worshippers in Afghanistan who had been blown up at their place of worship by Pakistani Sunnis. Most of the paper squares are mounted on hand-cut and sanded dowels of varying length so that image protrudes into the viewer’s space. Square mirrors embedded within the piece also implicate the viewer and integrate the colors and textures of our world.

A woman in green screams in the center of the image, and it is her mouth and part of her body that are left cohesive. It’s also this point that juts furthest into space. I titled the piece “Gaze of Orpheus” to imply our distance from her terror and open up a discussion about what it means to look at horrifying images in this digital age. Because of its fragmentation, even the parts of the original image that remain intact fall apart unless you confront them head on. I’m asking questions about what and how we see.

In this piece I appreciated that in the midst of processing the image by hand, Grumbine sought to translate the data visually so that all the information is still there — she’s just offering a new language. All language uses myths and symbols. Writer Linda. J. Busby delivered a speech titled “Myths, Symbols, Stereotypes: The Artist and the Mass Media” at the Annual Meeting of the Speech Communication Association decades ago, in which she said this:

Myths synthesize cultural history into majority beliefs and values. Both high art and popular art utilize these images, but the ways that popular art uses them are affected directly by structure, social worth, and social mobility. … Content can be viewed in terms of the physical and social structure of the medium, but there is also an important structural consideration in a work of popular art itself. Most observers of popular art define the inherent structure of that art as formulaic. By more carefully examining these images in popular art, we can learn more about values in society and about the various audiences to whom a particular kind of popular art appeals.

While exploring Grumbine’s exhibition, I couldn’t help but recall these words. I felt like the artist was saying that by more carefully examining these images in popular media, we can learn more about the perceived societal values that are being dropped into our consciousness. And then we can choose to dissociate ourselves.

Marshall McLuhan’s famous phrase “the medium is the message” proposes that a medium embeds itself in the message, creating a relationship whereby the former influences how the latter is perceived. Well, one of the media highlighted here is glitter, which for me has connotations of craft, ceremony, and femininity. That, along with the pace and medium of Grumbine’s art, reminded me of watching Tibetan monks work on a sand painting. Through precise, mathematical, and logical dissection, and with alchemical/shamanic ritual and ceremony, the work presents a vision of the future that lacks the past’s patriarchal aesthetic. It imagines, in a flash inside the flask, the opening up of a future with more feminine traits, and while doing so brings us through the act of reclamation and healing.