(published by Hyperallergic on June 26, 2013)

Brian Fernandes-Halloran, “Traveling North to Cabo Del Gado” (all photos courtesy the artist)

Upon entering 287 Spring to see Not Past: Old Toys and Lost Friends, a solo exhibition by artist Brian Fernandes-Halloran. one is confronted with two sculptural re-creations of toys the artist remembers playing with when he was growing up, a truck and a red hammer. Fernandes-Halloran’s work is composed of an array of found discarded objects and wax, and based on his memories as well as the broader concept of recalling and formulating memories. The truck he describes as his favorite toy, so he wanted the experience of re-creating it; the hammer, he explained to me, was interesting because his memory of it is abstract and vague. Recently he came across an old photograph of the exact moment with the hammer that he pictured in his mind. It made him question if he really had the memory itself, or if the memory was formed from seeing the photograph so many times over the years. Fernandes-Halloran engages in both a physical and psychological excavation process, with a deep interest in memories that may have been “dormant, subdued or not initially present during an experience.”

Brian Fernandes-Halloran, “Toy Truck” (click to enlarge)

Obviously Fernandes-Halloran begins his work from a personal place. However, since his materials are objects and debris he collects from his surroundings, he’s widening the conversation, both in the transformative way he uses those materials and in the fact that they have their own memories and histories.

The central piece in the exhibition is “Traveling North to Cabo Del Gado,” a full-scale truck he created from old wood, scraps of rusted metal, and broken glass. It’s a compilation of two separate but related memories telling two different stories. The back of the pick-up truck relates to an experience he had passing through a burning forest in Northern Mozambique. He was living and teaching there, and traveled north to paint murals, hitching rides on the back of trucks with strangers the entire way. He told me the rest of the story:

Many of the passengers were taking their first trip on a motorized vehicle. Some were moving homes, carrying all their belongings. There was always a sense of excitement among us. One of the trucks crossed the Zambezi River on a barge. The bridge was bombed a decade prior, during Mozambique’s civil war. North of the river felt like a different country. It was hit hardest by the war, disconnected from Westernized South Africa, mostly Muslim, and sparsely populated. One lucky day, a small family of a mother, father, and son and I bargained a ride on the back of a truck carrying corn. We traveled through the night across the sparse northern landscape. The father laid alone and fell asleep after a few hours. The boy sat on his mother’s lap facing backwards, directly in front of me as she embraced him. They did not speak English or Portuguese, but we looked at each other. The boy studied me for hours. We smiled at each other. As it turned to night, the mother fell asleep, still embracing her child. Her arms and head dropped.

The boy and I were too excited to sleep. There were no towns or lights for miles, and besides the truck’s light there was absolute darkness. There was a warm glow ahead. The boy saw the reflection in my eyes, and as we approached I could start to see him. He was frightened and placed his hands clenched on his knees. He did not move to wake his mother but looked directly into my eyes. What I learned later, he must have already known: farmers in the north burned forests to clear trees before planting crops. There was a blaze on both sides of our small dirt road ahead. The driver of the truck continued. We passed through the flames, exposed. We were bathed in light and warmth. The boy never flinched. When we had passed the flames he smiled at me, and then we slept. As many of my memories of Mozambique have faded over the past decade, this one has remained; maybe it has even strengthened over time. The fire may have gotten stronger, the boy closer. The assemblage of the truck has become a vessel for the memory, and I have changed the memory through the development of the piece. I am not in the truck to share the moment with the boy, as I have long left, but his mother remains. Over the eight-month construction of the truck, the mother has woken, the boy has relaxed his posture and his face. He even begins to smile. My memory is now of the two, comforted in their embrace.

Brian Fernandes-Halloran, “Not Past: Old Toys and Lost Friends,” installation view at 287 Spring

The second story in the sculpture relates to the passenger cabin. It began as a re-creation of the driver and passenger of the truck in Mozambique but transformed when two of Fernandes-Halloran’s closest high school friends died suddenly from accidents on separate mornings. On both occasions, he had been with them alone the night before and decided not to sleep over because of a minor disagreement. Fernandes-Halloran elaborated on this story:

One of them, also named Brian, had a car accident. I would have been with him in the car if I had not asked my mom to pick me up the night before. I imagined the accident so many times that it feels like a memory, though a memory would have been traumatic and violent; the imagining is calm and lamenting. Constructing the cabin with broken windshields triggered this imagined accident without me knowing it, and the figures began to evoke my lost friends rather than the driver and passenger of the truck in Mozambique. When I realized this, I began to switch the roles and make myself the driver and my lost friends a combined passenger figure. This resembles the present situation rather than an imagining of a past event. I now drive their memory. They have no physical selves to navigate their existence, but must trust those who loved them to guide them faithfully as memories moving forward in time.

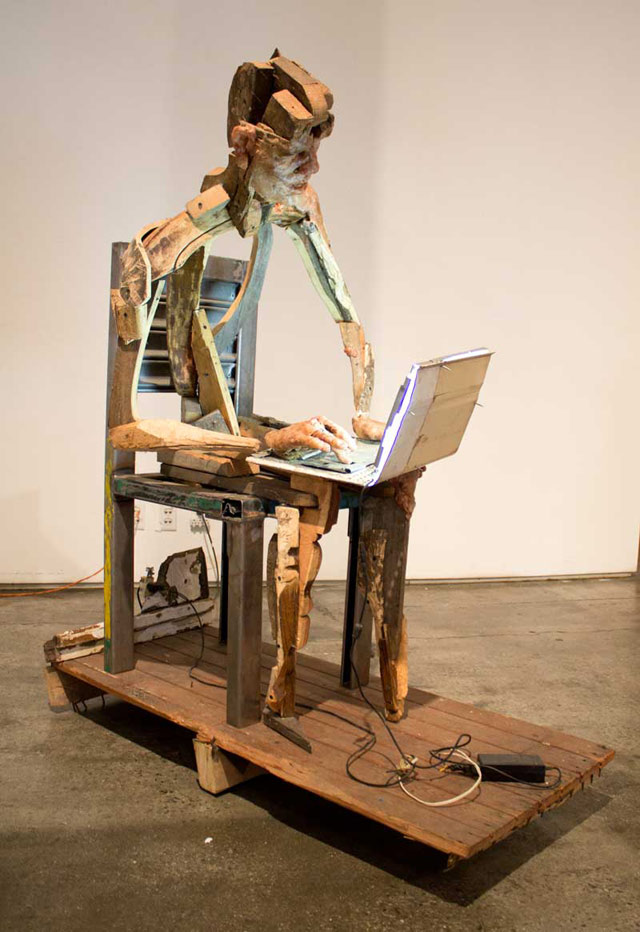

The show also features a number of other memory-related works, including “Saffron,” a reconstruction of his childhood dog (who was named Saffron), and “Browsing,” a self-portrait of the artist at his computer.

Brian Fernandes-Halloran, “Browsing”

I was struck most by the authenticity of the works, their humbleness and relationship to vulnerability. It feels like these stories want to come visually alive, like they aid Fernandes-Halloran in their own creation — rolling the right debris down the street where he happens to be walking. He operates intuitively, even subconsciously, throughout his process of gathering.

And the characters seem to be alive, even animated, despite what they’re made of. Fernandes-Halloran has a clear understanding of form, and he creates action-filled scenarios with only the skeletons of characters. “Browsing” is a good example of this: he provides just enough visual information so that we can both see the entire picture and allow our imaginations to fill in what is not seen, like reading a description of a character in a book. This balance calls to mind Diane Acherman’s description of Rodin’s sculpture “The Kiss” in her book A Natural History of the Senses. She writes, “Rodin has given these lovers a vitality and a thrill that bronze can rarely capture in its fundamental calm.” Fernandes-Halloran gives his sculptures breath and warmth, despite the materials they’re made from. He gives them a deep inner vitality, bringing to life discarded wood and making piles of refuse endearing, theatrical, and personal.

The artist’s work with memory is not only informed by personal experience, though. He researches psychology and neurology and is particularly influenced by the work of psychologist Elizabeth Loftus, who was part of the team that first proposed a widely accepted paradigm called the “misinformation effect.” The idea is that information accumulated after an event has occurred dictates how that event is (mis)remembered. Loftus’s work focuses on how memories are pieced together, often incorrectly, as they’re corrupted by new information.

Brian Fernandes-Halloran, “Saffron” (click to enlarge)

As part of the exhibition, Fernandes-Halloran hosted an event at 287 Spring with neurologist Dr. Todd Sacktor, whose lab at SUNY Downstate uncovered an enzyme that’s believed to be responsible for long-term potentiation, or the formation of long-term memories from our running short-term memory. Sacktor discussed the organic, emotional, and developing nature of long-term memory, and how Fernandes-Halloran’s installations tap into the hippocampus, the area of the brain that deals with special relationships and long-term memory through extended physical re-creations.

One definition of storytelling has it that stories are what happen between expectation and result. That dissonance adds an element of surprise that can jolt the reader or viewer into a heightened state of perception, and thus open up the mind to new ideas and perspectives. This is precisely what Fernandes-Halloran’s show did for me. I approached it wondering if the art might be overly sentimental, but what I found was a theatrical yet giving exhibition really engaged in a conversation about what it means to be human.