(Published on Hyperallergic on March 31, 2015)

Ondi Timoner is the only two-time recipient of Sundance’s Grand Jury Prize for documentaries, for her films Dig!, about the bands the Dandy Warhols and the Brian Jonestown Massacre, and We Live in Public, which focuses on internet visionary Josh Harris and how willingly we trade privacy, sometimes even sanity, in the virtual age. Both of these films are in the permanent collection of the Musem of Modern Art. A film director, producer, and entrepreneur, Timoner is also the founder and CEO of Interloper Films, a full-service production company based in Pasadena, California, that continually releases videos through an online video portal, A Total Disruption. The project focuses on people “using technology to transform our lives.” Timoner’s episode about artist Shepard Fairey premiered at the South by Southwest (SXSW) Film Festival in 2014, and an episode on the musician Amanda Palmer premiered in at last year’s Tribeca Film Festival.

I first became interested in Timoner’s work after learning about A Total Disruption, and, watching all of her films, I came to appreciate her dedication to telling many sides of a single story. She herself has said, “You can either love or loathe the subjects of my documentaries, depending on which part of the film you are watching.” I wanted to talk with Timoner more after listening to her TEDx talk, in which she describes her interest in visionary risk-takers, those people she thinks are crazy enough to turn their ideas into reality — there’s an aspect of them that needs to be a little impossible in order to push these big projects out into the world, she explains. She was as articulate and passionate about this in our conversation as in her talk.

Timoner’s newest feature film, on Russell Brand, was recently released at SXSW, as well as a short film called “The Last Mile,” about a tech incubator inside San Quentin Prison that trains convicts to be entrepreneurs. Preproduction has also begun on her new film about the life and work of photographer Robert Mapplethorpe.

Sarah Walko: One thing that stood out to me about the Total Disruption project is that it’s a strong empowerment and educational tool, a resource and database for innovators and artists. What was the impetus for you to start it? Who were some of the mentors or artists along your path, perhaps in your more formative years, who reached out a hand and guided your journey as a filmmaker? This project is so invested in helping other artists and innovators, it made me wonder if that was a big part of your history and how you got to where you are now.

Ondi Timoner: You know, I don’t want to throw her under the bus so I won’t say her name, but I reached out to somebody who I thought would be very excited to talk to a young woman filmmaker when I got out of college and when I was starting Dig! I reached out to this famous rock doc filmmaker, and she said, “Why would I want to go work with you?”

SW: Oh!

OT: Ever since then, I’ve been dedicated to helping anybody I can. I didn’t really have any artists that helped me except my subjects. I got my inspiration from the bands I worked with in the’90s and the making of Dig! I first got my inspiration from filming women in prison when I was a student at Yale — I would drive outside the prison walls with the footage and I would feel like I was participating in some kind of alchemy-like magic. Like I was creating some part of them inside some parallel universe that we support but that we have no view into the humans in there; they are shelved away. And then I would drive away with the footage of how they really feel and what they’re really about and just, you know, busting out the misconception. That really married me to documentary.

Then I made a film about one woman in prison that was supposed to turn into a TV movie out here, when I was 21. It was so distorted by the Hollywood process, and it didn’t need to be, and it felt like, how am I ever going to maintain my integrity and reach a mass audience with all of these people in between who were messing it up? That was what inspired Dig! I was looking at the collision of art and commerce, and I could look at it through all these nuclear families as bands who were on the verge of getting signed. That’s when I met the Brian Jonestown Massacre and the Dandy Warhols and David LaChapelle. Looking at their relationship to the record companies and to their art and fellow artists, and the jealousies and the things to do and not do — I learned all of that from those guys as my formative years as a filmmaker.

SW: So it’s a bit like your mentors were your peers and your subjects?

OT: Exactly, we grew up together. I think I’ve gained so much sustenance and wisdom and lessons about what not to do from watching their humanity under a microscope. I’ve honed my own relationship to the world as an artist, and I feel like I can share that with other people who are artists and actually empower them. So, any problems they’re solving, anything they’re tackling, entrepreneurs and artists, inventors, scientists, anybody I’ve ever interviewed for Total Disruption, eventually will be in this platform. We’ve also got a course coming out called “Lean Content.”

SW: Yes, I was reading about that and wanted to ask you about it.

OT: Instead of being a course that’s replicating a classroom, it’s really an attempt to make the first ever online course for content creators in general, on how to redefine the rules of engagement, how to make work in an interactive way, and how to reform our relationship with an audience that becomes a community, that becomes a family sustained over a career. All of that is from artist to artist inside this course. There are also many founders of disruptive platforms today that may or may not exist in five years, but it doesn’t matter — it’s the way they’re rethinking how we create, market, distribute our work, and finance it.

The motto is of A Total Disruption is “smarter, faster, together.” It’s like, let’s take the competition out of it and actually share our wisdom because that’s what the internet empowers us to do. It empowers each one of us to have a direct relationship with other people across time and space.

SW: You talk about the subjects in your documentaries as impossible visionaries, these cultural lightning rods that are there to embody transgression. It makes me think of the mythological trickster and the long history of that figure. I wanted to ask you, first, do you think of yourself this way — similar to some of your subjects, a cultural disruptor?

OT: Oh yeah, I think that’s what works, because I can completely relate.

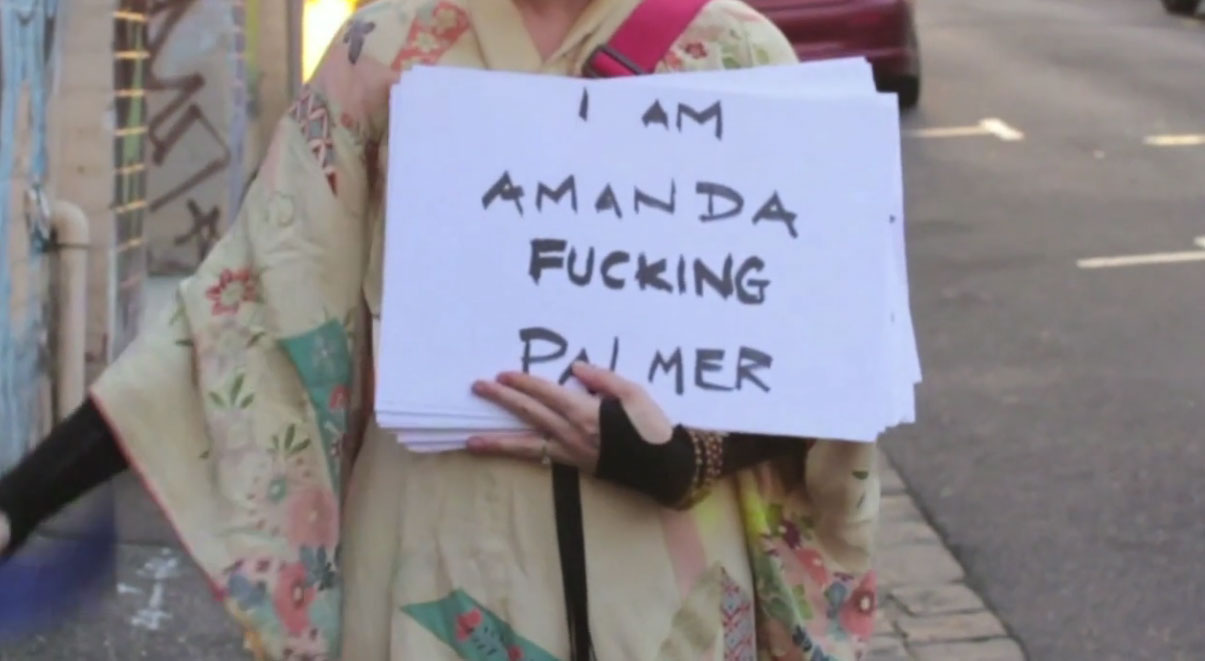

SW: Also, for example with Amanda Palmer, she has such a strong media-made personality, and there’s so much that you do in the documentary that really humanizes her. Is that something you aim to do?

OT: My entire reason for doing this is to humanize and make these people relatable. There are a lot of different participants, people that have founded major companies like Instagram or Twitter. It’s about the people who are watching, feeling like they can relate, that they could be that person. Have you seen my TED talk?

SW: Yes.

OT: So it’s about that: tracking the gene of the impossible visionary so that we can unleash that on ourselves, so that we can all learn to be impossible and stick with our vision and believe in ourselves. This world is too hard on us. There’s too much criticism when you try to do something outside of the box. There’s too many people that doubt along the way, and the only way to really make it happen is to be kind of impossible. And have tenacity and courage and look for signs and serendipity. Keep your antenna up and find collaborators and alliances with other artists, or foundations or patrons, who understand what you’re doing. Figure out how to relate to what you’re doing with integrity.

In this day and age, there is just so much noise. How do you disrupt effectively? The only way you can do that is by finding like-minded people out there, and that’s what we’re empowered to do now. We can find niche audiences because we don’t need to have the millions of dollars of return that studios demand. We can actually say, “Hey, here’s what I’m doing. Do you support me in this?” And you can bring that creation to everybody else, and it makes the world a little bit more how you think it should be. What influenced me the most was hosting my talk show, BYOD. That mentorship you’re talking about — I didn’t get it right at first from other filmmakers, but I get it all the time now because of the BYOD show. I get to see and visit and share a certain intimacy with my colleagues in a way that no one else does.

SW: Right, and you’ve been able to have these great one-on-one conversations with them all.

OT: I learned early on as a Yale student that when I went out with a camera and I started asking people questions, first of all, I would get much more nuanced information. Then I could cut that information together and share it with audiences on the public-access station that was in New Haven, Connecticut. This is where I learned to edit and where I put my stuff out. I told all the teachers, ‘I will only take your class if you let me make a film instead of write a paper,’ so by my senior year I made five.

SW: So, one thing in particular about these three artists you focus on for the Total Disruption shorts — Shepard Fairey, Amanda Palmer, and Russell Brand – is that they’re all equally operating in both a gift economy and the market economy, and they move fluidly through both in order to bring their work out into the world. They all have a strong sense of responsibility for giving back to their supporters and understanding of the role of reciprocity in community building. I was wondering if it was this aspect that drew you to them, that dedication to giving?

OT: They’re all revolutionaries — they’re all completely trying to change our relationship to culture, to not be passive receivers of that culture. And I think each one of them is not satisfied, as I’m not satisfied, with just making work within the status quo that maintains the status quo. And they go about doing that in different ways. Take Amanda, for example — it’s not magic or a coincidence that she had the biggest Kickstarter in music history. She motivated that, she worked for her community. She answers everybody on Twitter and Tumblr and Facebook, and she makes them feel human. She empowers them to quit their jobs and become artists.

She gives so much, but she asks too, you know. By asking people to be involved, you’re giving to them; you’re opening doors for them inside their own mind and their own lives. And that’s what Russell is trying to do right now, too — he’s trying to get people much more involved in politics and in shaping their own futures. He’s trying to move governments.

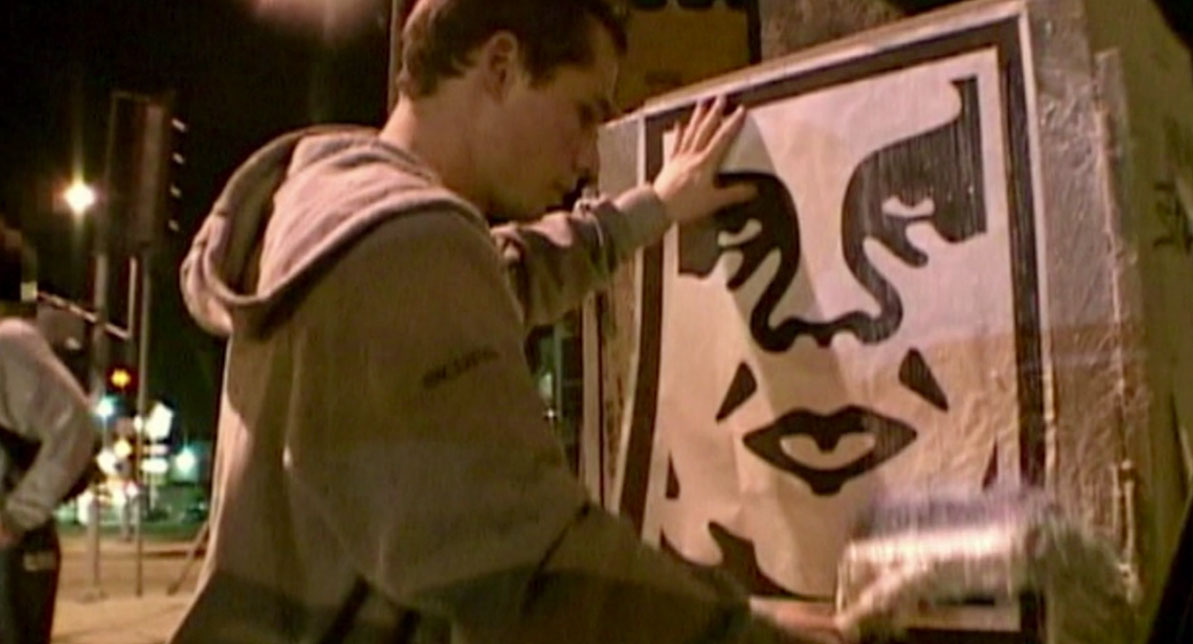

Shepard did a show in Chicago with 45 artists recently, a collaborative show. It was at a gallery where he curates, and he only has the freedom to do that because of his clothing line and because of the internet. The Obama Hope poster went viral because he put that in the hands of people and allowed people to share it and use it and make it their own in their own communities. He’s often criticized for the way he pulls the veil back on the art world and disrupts, you know? But that’s who he is. He was raised on punk rock, and he is determined to do things the way he feels they should be done. Trusting that instinct against these systems is really, really important for all artists to do these days. Everybody needs a little Amanda, a little Shepard, a little Russell in their spirits. These people say, ‘how am I going to do that?’ and just figure out how to do it. Amanda and I came up with this term — I can’t remember which one of us coined it, but its “doshitism.” I love that.