(published December 15, 2009 on Hyperallergic)

I have a number of ritualistic acts within the process of making my work. I go on walks through parks and thrift stores and collect small things. I spot objects on the street and in subway stations that I snatch and put into the small plastic bags that I keep on me at all times. At the end of the day, the tiny collections are emptied onto my workbench, joining many other materials and objects which are found, made, or given to me.

The matchbook is an apt container for the size of objects I often work with but also is a symbol of potential light, therefore, a perfect canvas for tiny worlds and words. I determine the phrases and color of the words and have them printed and then add objects and images, making each its own unique sculpture. I install them in exhibitions and place them inside shadow boxes however, the true life of these works is when they are re-released. I drop them in subway stations, at friends’ houses, in parks, on doorsteps, benches, phone booths and in bookstores.

I also drop my sculptures in more prestigious places. I have unofficially placed them in many institutions all over New York and surrounding areas such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, MASS Moca, the Morgan Library Museum, the American Museum of Natural history, the Rubin Museum of Art.

I have no idea if it is a visitor, a curator, a janitor or an insect, that might happen upon these sculptures first and/or finally nor does it concern me. In my mind, they become like fictional characters in a story having adventures from that point on. I also place them at statues and landmarks around the city, such as on the doorstep of the narrowest house in New York in the West Village, former home of writer Edna St. Vincent Millay.

I had a friend of mine walk into the house of her close friends to find one of my matchbook sculptures framed and in the living room décor. Upon exclamation, “Oh! You know Sarah?” They reply “No. We just found that”. I also have a very close friend who had a girlfriend he had been wanting me to meet for quite some time but our schedules never aligned. He met her once in the city and when he did, she was holding one of the sculptures. He exclaimed, “Oh! You met Sarah?!?!” And she replied, “No, I just found this”.

My favorite part of the process has been giving them to friends to give away on their travels. A friend, Thaddeus

Pawlowski, recently took a trip to Nepal to hike the Himalayas for one month on a spiritual pilgrimage. Below are two excerpts from his Nepalese journals:

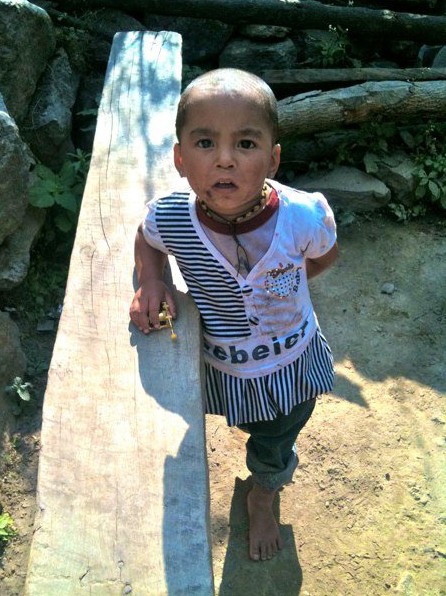

I was walking along a high ledge over the Marsyangi River Gorge in Central Nepal, at the base of the Annapurna range of the Himalaya [range]. There are many shrines along this trail, and it is expected that locals and travelers leave important objects at them. This is to appease the mountain gods who often smite the proud with landslides and erosion. On the mountain across, men were jackhammerring away at the granite, building a road, producing a horrible sound that echoed everywhere. I stopped for a rest and a ginger tea at a little shack where a group of porters were playing cards. A little girl — maybe about three years old–crawled up to me. Her head was unevenly shaved, probably for lice. I could only assume that she lives her whole life here in this shack with these men. In my backpack I was carrying a concert of objects passed on to me from Sarah Walko. Each of these objects was arranged carefully in small fugues and bound to a matchbook. I pulled out one matchbook with a very small music box that played “Hey Jude” attached to it. I removed the music box from the matches (she was too young for those, but I gave them to an older boy in the next village). I could see that she knew it was important and she would keep it and learn it. I turned to the group of men and held up the box and motioned that I was giving it to her. They nodded. Sarah’s work came to this girl, to give a little bit of private harmony in this noisy place.

Another sculpture found a nice home in the ancient village of Lubro, a few miles up in the mountains away from the Kali Gandaki Valley, the holy city where all five elements meet. We wanted to see Lubro because it is one of the few remote villages left where they still actively practice the b’on religion, an animist belief system That predates Buddhism here by ten centuries. The b’on worship all aspects of the mountains. We had a tough but thrilling walk there, high up into the clouds, passed singing goat herds and bright red wildflower[s], onto a plain that opened up the clouds all around, with grassy knobs on both sides, it felt like the entrance into another world, then we came down through rock fields with cephalopod fossils everywhere, pushed to these mountaintops from the bottom of the sea when the Indian plate crashed against the Eurasian plate 50 million years ago. The Hindus thought that these serpentine creatures were evidence of the god Vishnu. The villagers stared at us in dumbstruck confusion. We explained that we came to see the b’on monastery. An old woman let us in and we studied the ancient frescoes and sculptures. Taking notes on the strange iconography. This is where the swastika comes from and many other mysterious symbols. Another old woman invited us for tea, as neighbors butchered a goat on her roof. She taught us b’on mantras and gave us milk tea. I gave her a matchbook with a feather and the blue rocks. We talked about the elements it might represent. She held it in both hands and kissed it and put it up in her cabinet …

The objects we surround ourselves with and the rituals we do in our everyday life are too often dismissed as arbitrary or marginalized when in fact they affect our individual and collective psyches tremendously. Anthropologist Margaret Meade said, “When justice is lost, we have ritual. We need more ritual in our daily lives.” The entire process of these small sculptures from beginning to end is my ritual. The object then carries that process within it and interrupts the flow of the environment and perception of the viewer like a tiny seed or crack, the mysterious evidence of this string of acts. This allows me to move fluidly between and within private and public space. Similar to a book, finding and reading a matchbook is an intimate yet vast experience. A reader and an author have a conversation between two which expands and/or collapses time, regardless of the surrounding space, and has the ability to be incredibly personal or shared. The matchbook as an object can pull one inside to a tiny world and words, like a little pocket inside the reader or the author’s mind or push the reader back, the scale of the object so small that the viewer is huge, the master of a small world. Ultimately, I hope it does both, and one can fluctuate between micro and macro as well as bring the reader to the present and simply say, “You are no where else right now but here and this is the invention of questions.”

Recently, at my workstation, I came to the end of my box of custom printed matchbooks. As I finished the last few, I realized, when I placed the order, I did, in fact, order 3000. Therefore thousands of matchbook sculptures are out in the world. I don’t care if they are mounted and framed on mantels, nor if the music boxes are removed from their compositions in order to give to a little girl who is too young for their container. I hope they are used for exactly what they are supposed to be used for, to light a candle or a fire until they are completely used up. I want them to question the idea of the precious collection and the unnoticed accumulation of vacant things, be it in a museum or product in a store. They are created and destroyed, come and pass and a simple container for ideas and spirit in flow. Placing them all around New York City and all around the world completes the cycle of gift exchange, as so often the object I place inside of them, come to me first. They are pocket sized, to fit in the palm of the hand of the finder, the keeper, the dreamer, whoever or whatever happens upon them.

Everybody needs a little light.